More Power!

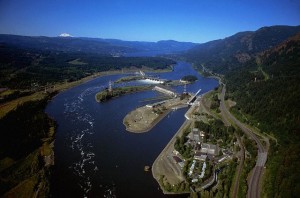

I live in the Pacific Northwest and have seen or visited several of the hydroelectric power dams along the mighty Columbia River.

Hydroelectric power accounts for nearly three-fourths of the northwest’s electricity generation, the most in the nation. For years, Pacific Northwesterners enjoyed relatively low electricity costs. I can remember our boasting about a penny a kilowatt when the rest of the nation was paying five times that.

Unfortunately, for reasons beyond my understanding, we are now paying our “fair share” and more in alignment with the rest of the nation. And we’ve even experienced so-called power shortages; never totally understood that either.

All that aside, the dams along the Columbia River are an engineering wonder. The very well-written article below does an excellent job of describing just what a wonder the system is. It’s quite long, so I’ve only posted a portion of it. But please click the link to read the complete article. It’s well worth the time.

The High-Stakes Math Behind the West’s Greatest River

Jon Bruner, Forbes Staff

In the generator room at the Bonneville Dam. From left: Rick Pendergrass, Jim Duffus, Witt Anderson, Jerry Carroll, Harold H. Opitz. Photo by Robbie McClaran for Forbes.

In a darkened, ultra-secure room on the fifth floor of an unassuming office tower in Portland, Ore., Bob Neal sits before a panel of ten computer screens and plays Moses. It’s 8:45 in the morning on a sunny late-August day and electricity demand is rising as office workers across the West switch on their computers. Neal points to a dense blue-and-white display whose flickering numbers show power output at each of 31 dams in the Columbia basin. With a few keystrokes he orders the Grand Coulee Dam, the continent’s largest power plant, to ramp up its output by 870 megawatts in the next hour—an increase enough to light 15 million light bulbs at 60 watts apiece.

240 miles away, the Grand Coulee’s 24 giant turbines ease open, sending a surge of water toward the Pacific Ocean. Just below the dam, the river quadruples in volume and rises by 13 feet over a period of nine hours. By 2 P.M., one and a half million gallons of water—enough to flood a football field three feet deep—moves through the dam’s turbines every second.

The Columbia is a river of colossal proportions: it’s the most voluminous in the West, draining an area the size of Texas and each year passing 60 cubic miles of water to the Pacific Ocean. The 14 structures that harness it are equally formidable: a dam is likely to be the largest manmade object, the most exuberant feat of engineering that you’ll ever see, and the Columbia’s are among the world’s biggest. But as large as the dams are, their margins are minuscule and operating them takes unerring foresight and subtle management: let too much water fill reservoirs and a rainstorm might flood Portland; keep the reservoirs too empty and you’ll parch farmers. Send too much water over a dam’s spillway and you’ll suffocate fish with dissolved gases; send too much through its turbines and you’ll overload the electrical grid.

Those margins are doubly difficult to master given the temperamental pulse of a river whose volume increases by a factor of five every spring as snow melts in the Rockies. Within the river’s seasonal changes come manmade fluctuations: every morning its dams awaken the Columbia with surges of water to satisfy the Northwest’s demand for electricity, and every evening the dams tighten their gates to put the river back to sleep. And every other second, an automated system assesses the supply of electricity against demand and makes tiny adjustments to the volume of water moving through each dam’s turbines.

The Bonneville Dam’s Powerhouse No. 1 is a thousand-foot-long, depression-era edifice that bristles with electrical transformers and transmission lines. It sits astride the Columbia River, which loses as much as 70 feet of elevation as it falls through the building’s turbines and emerges, almost glass-smooth, in the powerhouse’s tailrace. In the generator room, a space so long that its horizontal lines converge and fade into the distance, ten school-bus-sized generators hum quietly. “It’s big, isn’t it?” says Jim Duffus, the power plant’s ebullient, moustachioed manager, as he strides down the broad corridor. Duffus started out as an electrician’s apprentice in the Panama Canal Zone, and his enthusiasm for all things electric and for the scale of the place emerges in his narrative. That’s not just a circuit breaker; it’s a five-ton circuit breaker.

Each generator housing contains a 280-ton turbine that looks like a ship’s propeller and a 430-ton generator rotor that spin in perfect synchronization with the grid’s alternating current. As large as these generators are, they’re among the nimblest big sources of power available: Duffus can bring a turbine online in under two minutes and, once it’s running, can summon as much electricity from it as he needs in as little as ten seconds. Each 60-megawatt generator can produce enough electricity to supply roughly 60,000 households, but all of that capacity isn’t needed most of the time.

For the full article, please follow this link: Forbes

Tags: technology